Whether it is 90% or 96% of our thinking is unconscious, depending on who you ask and how you measure it, the more important matter is not the number, but the fact that most of our thinking happens below the surface of our attention.

It seems such a simple and yet revealing insight that most of our work with audience engagement, motivation, fundraising, campaigning, or any aspect of working towards a cause, prioritises conscious thinking, sometimes to the absolute neglect of our unconscious mind.

It is why we get so frustrated by the seemingly paradoxical behaviour of audiences who will, when prompted, tell you how much they agree and support your cause, but then fail to show up, sign up or get involved in any real and meaningful way. We also get frustrated when we clearly make the case, the rational case that is, for why we need to take urgent action on our collective causes, but then experience widespread apathy when it comes to doing anything about it.

It seems that the problems we regularly encounter are to be found below the surface of our attention, and if we are to overcome them then we need a better understanding of the unconscious mind, and how to engage with it in our work.

Neglect of the unconscious mind

When we think about it, it is remarkable that we rarely speak of or reflect on our unconscious thinking. We might not even refer to the unconscious mind outside a medical or therapeutic setting – in other words, only when things seem to have clearly gone wrong from a medical perspective that we ever seem to make an effort to consider this dominant aspect of our thinking.

But our unconscious mind defines our thinking, beliefs, who we are, our values and how we relate to each other and the world around us. Ignoring this significant aspect of the self comes at a great cost in terms of understanding how motivation works, how to create meaningful change on social and environmental issues as well as how to create long-term behavioural change. When we lack an understanding of what makes up 96% of our thinking, then we should not be surprised when we encounter huge obstacles in our work when trying to engage and motivate audiences to take action on the causes we care about.

How do we make sense of apathy and indifference to issues that people seemingly care about? Why do we experience so much polarisation in our work? Why do people who care passionately about the causes we champion, but then react negatively when we try to engage them? These are all important questions, and what is frustrating, is that when we ask audiences the reasons for their behaviour, we struggle to find any meaningful answer.

Because we are dealing with the unconscious mind, we are dealing with deep-seated issues that any audience research will struggle to reveal. Trying to find answers to human motivation using our ‘conscious’ and rationalising mind will always struggle to find answers to the paradoxical conditions of human nature.

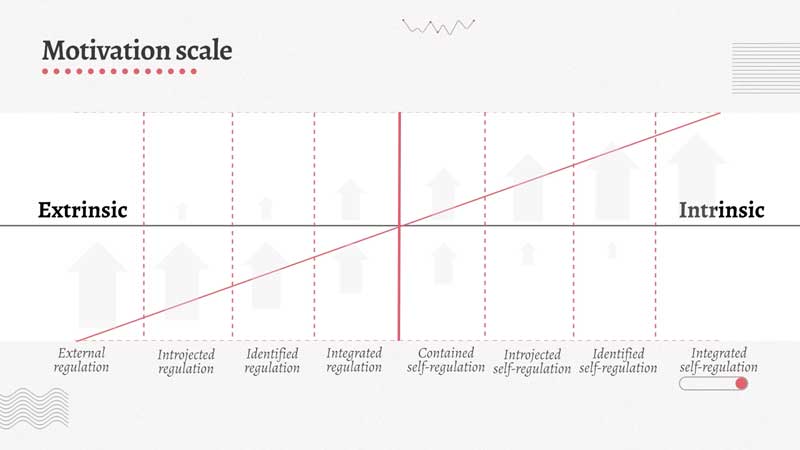

If we are serious about bringing about positive change in the causes we care about, not only do we need to understand our unconscious mind, but we must be able to work with it in some way. Only by doing so can we begin to address some of the perennial issues around low motivation that we regularly face, and only by doing so can we take our audiences up to the higher stages on the motivational continuum, where we can work with the unconscious motivational triggers that lead to long-term behaviour change.

Our unconscious mind defines our thinking, beliefs, who we are, what our values are and how we relate to each other and the world around us. Ignoring this significant aspect of the self comes at a great cost.

Kieran O'Brien - Director of Ministory Tweet

But the challenge we face is that we tend to have a very limited, if not impoverished understanding of our interior selves and how the unconscious mind really works.

The result of which is that we tend to view the unconscious mind as some dark and scary place, somewhere where we might be very reluctant to explore or even think about. Who knows what terrors lurk beneath the surface? It’s probably best if we keep the door to the unconscious firmly shut.

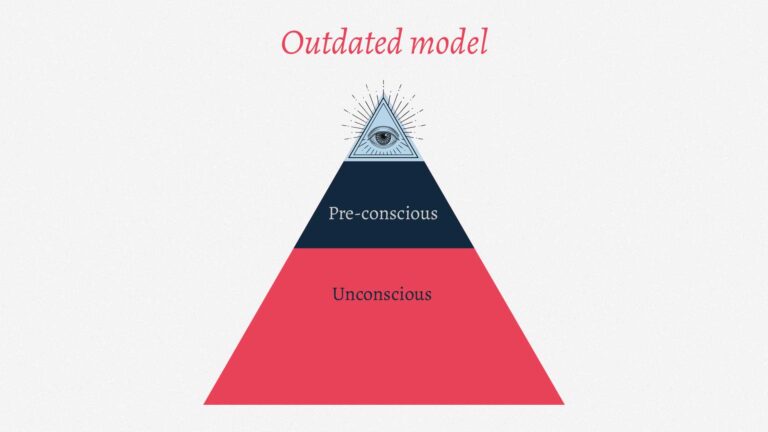

But most of our thinking on this matter is shaped by an outdated model of thinking, that can be simply summarised as the control-tower mode of thinking.

This model of thinking places the rational thinking mind at the top, and places the pre-conscious and unconscious mind below.

We can draw some links to the philosopher Rene Descartes, who famously said “I think, therefore I am”. This places the rational mind, the “I” that Descartes refers to, in charge, and casts a sceptical eye on all other modes of thinking, including intuition, imagination and emotion as untrustworthy. In other words, all the aspects that differentiate us from a machine or computer, that which makes us human, we should be sceptical of.

Without going into a rabbit hole of philosophical enquiry here, we should just draw our attention to the limits of this almost universally agreed model of thinking (this is called the Cartesian paradigm, which we cover in our Beyond the marketing paradigm training programme), the result of which is that we promote and celebrate rational thinking, and neglect all other forms of non-rational thinking.

Breaking this model is necessary if we are to shine a light of clarity on the unconscious mind, and use a different model to approach our ‘unconscious’ mind, and to find insights that can help us solve some of the greatest challenges we face in our collective work.

Beyond the control tower model of thinking

Descartes’s insight might seem like a useful insight, especially from the perspective of the rationalising mind. This is where we get into a paradigm trap – the rationalising mind sees itself in charge, and, as a result, reinforces the paradigm that it is in charge. But we now recognise that this model of thinking has caused so many of the problems we see today. Our collective over-reliance on our rationalising mind, and neglect or suppression of all our other modes of thinking, can lead us to embrace the values ecology of the rationalising mind that cause so much harm to our world.

When we look at African indigenous tribes, the dominant paradigm is not ‘I think, therefore I am”, but rather Ubuntu, “I am, because we are”. In other words, what makes the “I” is not an individual, separate being, but rather the “I’ cannot be seen as separate from the community and surrounding environment. This shift in paradigm nurtures a different set of values, and it is no surprise to see communities and tribes living under the Ubuntu paradigm showing high pro-environmental and pro-social (or rather, pro-community) behaviours.

As we struggle to live in harmony with our natural environment, as well as with each other, clearly we need to move beyond technical solutions and to seek what has gone wrong with the paradigms that we hold to be true. Clearly, something has gone awry with the way we think.

Understanding how we actually think

This is where the insights from psychiatrist, neuroscience researcher, philosopher and literary scholar Iain McGilchrist can help us. In his first book, The Master and his Emissary, on which the above animated short story is based, we discover a set of stories that have emerged across different cultures and times that represent this pattern of master and servant, when the servant takes over the kingdom and falls into ruin. It is an extraordinary pattern that intuits the nature of the two hemispheres of the brain.

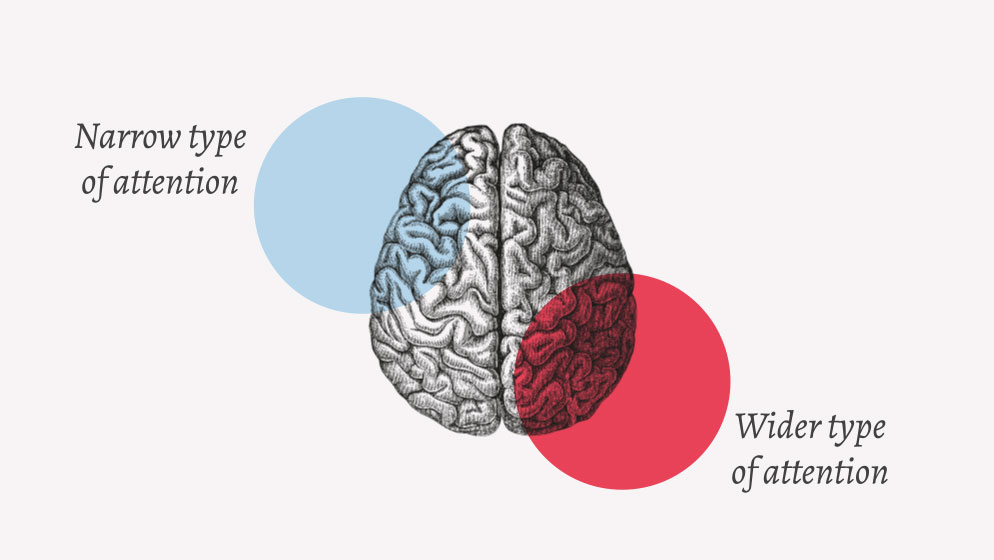

His contribution to this complex area of academic research can be summed up by one simple insight. It is not that the two hemispheres do different things, i.e. one does analysis and the other one does creativity, but rather that they both do everything together, but differently. There are two different natures to the two hemispheres, and how they work; two different value systems, and two different ways to interpret reality. Understanding these differences offers a wide range of profound insights that have huge implications for all of our work when it comes to working with human motivation.

Using our story above, the right hemisphere is the master. It sees all, it understands context, implicit meaning, relationships, metaphor, humour and so much more. But the left hemisphere, the emissary, thinks that it is better than the right hemisphere. It mistakes the wisdom of the right for foolishness and sees it as weak. But when it takes over, the kingdom falls apart. The left hemisphere is goal-orientated, has narrow attention, deals in abstract ideas rather than reality, and is self-absorbed and dogmatic.

The left hemisphere knows how to grab, manipulate, and seek power but doesn’t understand context, meaning, purpose and all the important things that make us human. It acts more like an efficient robot than a human.

In his second book, The Matter with Things, McGilChrist then goes into huge detail to show how our society has moved to the left hemisphere way of thinking. As in our story, the emissary has now taken over, out of which our world is falling apart.

Understanding the divided brain helps to show how there is a whole piece of work with the right hemisphere that we are totally missing in our collective work, which has serious consequences for driving real change and creating impact.

There are too many insights to list here, which are covered in detail in our training programmes below, but we can broadly put it as simply as this, when working with the left hemisphere we lean towards extrinsic values, extrinsic motivation and extrinsic purpose. This can create short-term results but is terrible at creating long-term change.

No organisation is exempt from this. Our research on climate-related communications that there is a clear and significant shift towards the lower ends of the motivation continuum and towards extrinsic values. The result of this is not only that we struggle to engage audiences, but we also risk undermining our work towards the causes we care about.

The left hemisphere works with a narrow type of attention, it is good at analysing and breaking things down, but cannot understand the whole. The right sees the big picture, works with the implicit, deals with embodied knowledge, and is the more intelligent hemisphere.

Consciousness is like a broom closet in the mansion of the brain

David Ealeman, Neuroscientist Tweet

Working with the unconscious mind

Understanding the implication of the insights from hemispheric lateralisation (understanding the different functions of the two hemispheres of the brain) offers a whole new suite of insights and new approaches to audience engagement on a whole range of social and environmental issues.

Understanding how we think, the dominant paradigms we hold, and how to work with the values system of the right hemisphere can offer profound insights that can help us overcome some of the greatest challenges we face when it comes to the perennial problem of motivating audiences into action on the causes that we care about.

Shifting our work to focus on the language, values and motivational triggers that sit with the right hemisphere, is our urgent task if we want to overcome the perennial problems of audience engagement and motivation.

But to achieve this ambitious goal, we need to be willing to work and think differently. This means leaving the comfort of our dominant paradigms, including our control tower thinking model, and embracing new models of thinking, where we pay more attention to the non-rational aspects of thinking. This shift in attention can help us to look afresh at some of our communications and engagement strategies, and see how to align them to the motivational triggers found on the right hemisphere. In other words, how to work with intrinsic motivation, intrinsic values and intrinsic purpose.

The potential here is huge. If we were to abandon the Cartesian paradigm of “I think, therefore I am”, and embrace alternative paradigms to shape our thinking around audience engagement, then we can open up a whole new eco-system of methodologies, toolkits and resources that can help us address audience motivation in an entirely different way.

When we stop treating audiences as rational decision-makers or playing to people’s fears and anxieties to drive motivation, we can start to embrace new methodologies that work towards the higher stages of the motivation continuum. These stages cannot be accessed through a marketing mindset, nor a face-to-face encounter, but only through storytelling and a shoulder-to-shoulder encounter.

Integrating insights from McGilchrist’s work, and how to work with the dynamics of the right hemisphere will take time to learn and implement into our work. This means working together to build up a new motivational ‘engine’ based on storytelling dynamics. This is the shift from the marketing paradigm to the storytelling paradigm, which is a necessary shift for all organisations, movements and individuals who are working to bring about positive change to our world today.

To find out more, check out our online self-directed training programme below.

Insights

- Most of our thinking is unconscious, and yet rarely do we ever speak about nor take into consideration the unconscious mind in our work. The results of this huge oversight mean that we tend to focus all of our work towards the rationalising mind, which results in strange paradoxes in audience behaviour – where audiences will agree with what you are doing but fail to engage in any meaningful way.

- There is a clear correlation (which is explained in detail in our training programmes below) between the ‘rational’ mind and extrinsic values and extrinsic motivation. Engaging these motivation and value types make it almost impossible to bring about long-term behaviour change, and will ultimately undermine all of our work towards the causes we care about.

- The control tower thinking model, where we view ourselves as rational decision-makers, is an outdated model. Embracing it distorts our understanding of how we think. The result of this is significant, as we will tend to make rational and compelling reasons why we need to take action on the causes we care about while failing to address the relational aspects of human motivation. This is why we struggle to create the motivational pull to drive audience behaviour.

- McGilchrist clearly shows in his research that our wider society is increasingly moving towards the left hemisphere’s take on the world, resulting in a whole range of issues. The left hemisphere cannot think outside the paradigms it creates for itself, this is where we create the paradigm trap. This is why we find it difficult to solve some of the problems around motivation and values dissonance (when we try to extrinsically motivate intrinsic values, resulting in creating dissonance in our work).

- By understanding the nature of the two hemispheres and how they work, we can avoid the trap of only working with the left hemisphere (rational). Our ability to work with the right hemisphere can help us to work with intrinsic motivation, intrinsic values and intrinsic purpose -which are all necessary if we want to create real change on the issues we care about.

- The right hemisphere works with the implicit, while the left hemisphere works with the explicit. To work with the implicit nature of storytelling means that we need to learn how to work with metanarratives. This requires a different skill set which we call Master Storytelling.

- Working with the right hemisphere demands a shift from marketing theory to storytelling theory. This is a paradigm shift, and understanding what paradigms are and how to transcend them demands specialist training.

Solutions

Understanding and working with the unconscious mind is essential if we are to bring about the changes we seek on the causes that we care about. There is a lot of work here to make sense of McGilchrist’s work and insights, and how to apply this to our work will take time. But the wins here are potentially huge. If we know how to work with the right hemisphere we can overcome some of the greatest challenges we all face in our work, especially polarisation, low motivation, apathy, declining engagement, declining income, low participation rates on campaign activities, and so much more.

- Understanding how the unconscious mind works and how to engage with it can provide some incredible insights into audience motivation and behaviour. These insights are essential if we are to create meaningful change on the causes that we care about. Our online, self-directed training programme Storytelling and the unconscious mind will provide you essential insights in which you can apply in your work.

- Understanding the unconscious mind, and how it connects to storytelling theory, values theory and motivational theory is explained in our full storytelling training course (see below). We recommend this training course for everyone looking to engage and motivate their audiences into action on their cause. Although the focus of this course is on climate activism, the core principles can be applied to any cause.

- You can check out our YouTube channel for talks, explainers and other content that relates to working with the unconscious mind.

Our full online training course

New training programme.

Become a Master Storyteller with our specialist 13hrs+ online training course

Motivation theory

Explore a new approach to motivational theory and how to work with intrinsic motivational triggers

values theory

Insights into values theory and how to work with the flow of values and their relationship to each other

neuropsychology

Utilising insights on the different values systems of the two brain hemispheres and how to apply them

storytelling

Learn how to become a Master Storyteller, someone who can create powerful metanarratives

Storytelling training programmes.

These online, self-directed training courses are full of specialist insights, toolkits and methodologies that are designed to help you to create meaningful change in your work.